Ready to Master the Art of Persuasive Communication? Unlock Your Success Today!

Today I’m going to cover domicile in Private international law.

Here I will discuss;

Let’s get started

Jump to section

Transform Your Communication, Elevate Your Career!

Ready to take your professional communication skills to new heights? Dive into the world of persuasive business correspondence with my latest book, “From Pen to Profit: The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Persuasive Business Correspondence.”

What You’ll Gain:

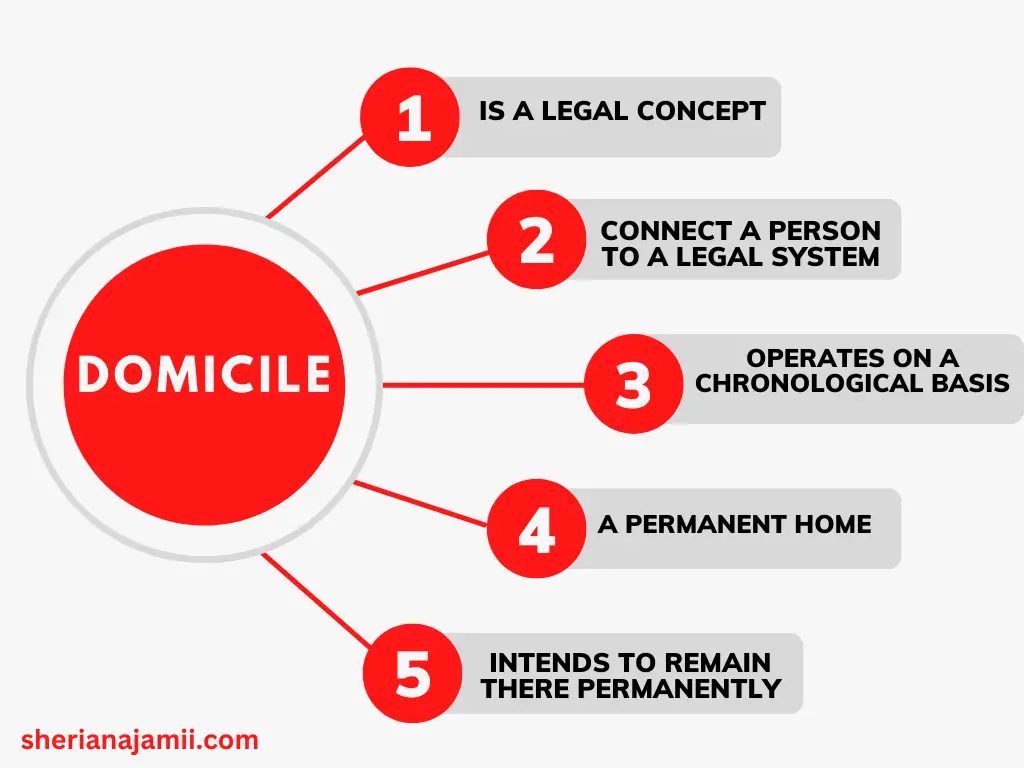

Domicile simply means a permanent home of a person. It may be defined as the legal system within whose jurisdiction an individual makes his or her home, intending to remain there permanently.

Domicile is a connecting factor that links a person with a particular legal system and the law of his domicile is his personal law.

That law determines, in principle, whether a man or woman has the legal capacity to marry, and how the estate of a deceased person is to be distributed.

If a married person is domiciled in England, the English courts have jurisdiction to dissolve or annul his or her marriage.

If a married person is domiciled in, say, France, then a divorce decree granted by the French courts to or against that person will be recognized in England.

Five important things about a domicile can be drawn from the above meaning.

A country of domicile means a country within which a person makes it his or her home and intends to remain there permanently.

It is not necessary for the country of domicile to be the country where a person was born.

These general principles were first clearly enunciated by Lord Westbury in Udny v. Udny in (1869) 1 LR Sc. & Div. 441 HL.

A domicile is attributed to a person by law as his domicile of origin or of dependence.

He/she will keep such a domicile unless and until he attains another by choice, and if he abandons a domicile of choice his domicile of origin will revive and be his domicile unless and until he acquires another domicile of choice.

This inability of anyone to be without a domicile makes domicile preferable as a connecting factor for determining the personal law to any other, since a person can be without a residence, a home, or a nationality but not in the case of domicile.

In Mark v Mark [2005] UKHL 42 at 37, it was illustrated that

a person may at least have a domicile of origin at his birth, if he is a legitimate child, the domicile of his father, if he is an illegitimate child, the domicile of his mother, if he is foundling, the place where he is found, this domicile prevails until a new domicile has been acquired. If a person leaves the country of his origin with an undoubted intention of never returning to it again, nevertheless his domicile of origin adheres to him until he actually settles with the requisite intention in some other country.

Justification for this rule can be found in Mark’s case as cited above.

The aim of the law is to have a definite legal system that can apply to a person, therefore, is impracticable to allow a person to possess more than one domicile.

Domicile connote connection with a single system of territorial law does not necessarily connote a system that prescribes identical rules for all classes of persons it may have different rules applying for different classes of persons within one territorial law.

There is a presumption in favor of the continuance of an existing domicile. Therefore the burden of proving a change lies in all cases on those who allege that a change has occurred.

The standard of proof is that which is used in civil actions-on balance of probabilities.

The domicile of a person will be determined according to local law and not a foreign concept of domicile.

This was insisted in the case of Lawrence vs. Lawrence (1985) that subject to the statutory exceptions, the domicile of a person is to be determined according to the local law and not the foreign concept of domicile.

There are three forms or types of domicile, which include domicile of choice, origin, and domicile of domicile.

Domicile of origin is a form of domicile which is acquired by birth. In most cases, a child acquires the domicile of his father.

Domicile of origin depends on the domicile of one parent at the time of birth, and not where a person is born nor where parents were residing at the time of birth.

This attributed domicile is indelible and remains with the person throughout his life, even if for much of the time or, indeed, always, it is overlaid by another sort of domicile. It is very difficult for a person to lose this kind of domicile.

An example in the case of Winans v Attorney General, [1904] AC 287 in which William Winans who was born in Baltimore USA in 1823 and live there in 1859, went to England and lived there all his life at various places until his death in 1896, he lives in England for almost 37 years.

He built railways in Russia and helped that country in the Crimean War (1853–56) by constructing gunboats. He retained plans for his properties in Baltimore. He disliked England and appeared to be without friends.

The evidence indicated that his sole remaining ambition was to enable the USA to acquire world maritime supremacy at the expense of England. On his death in 1896, the question arose as to his place of domicile, in judgment Lord Macnaghten emphasized that domicile of origin is more enduring than the domicile of choice.

Domicile of origin as a tendency of revival in a case where one loses other types of domicile the domicile of choice or dependency, it never totally lost, if one acquires a new domicile, we may say it performs a gap-filling function if a person appears to be without a domicile then domicile of origin revives, this was clearly indicated by Lord Westbury word in Udny v Udny where he said that;

“as the domicile of origin is the creature of law, and independent of the will of the party, it would be inconsistent with the principles, of which it is by law created and ascribed, to suppose that it is capable of being by the act of the party entirely obliterated and extinguished”

In the same case, it was indicated that the domicile of origin of a child born under wedlock (legitimate) depends on the domicile of his father, and the domicile of the mother if illegitimate.

From the discussion above it follows that the factor used to determine the domicile of origin is depend on the domicile of his parent, the father if the person is an illegitimate child, and the mother if the person is an illegitimate child.

The domicile of the parent or guardian is one that takes into consideration in determining the domicile of origin.

But this domicile may be abandoned or lost by the acquisition of a domicile of choice, as what Colonel Udny do to his original domicile of Scotland after abandoning it and acquiring England’s Domicile.

Domicile of choice is a form or type of domicile in which a person after attaining the age of majority will have the right to acquire a new domicile in substitution for that which he has at present possessed.

For instance, If S is a domicile of Malawi and later on has an intention to live in Zambia and then, later on, have a residence in Zambia without the intention of returning back to Malawi, then S will acquire the domicile of Zambia as her domicile of choice.

There are two requisites for the acquisition of a fresh domicile(domicile of choice)thus residence (factum) and intention(animus) it is of at most importance that the person in question established his residence in a certain country with the intention of remaining there permanently.

This refers to physical presence in a certain country in which a person intends to be a resident. Long residence and short do not prove or negate domicile.

However long residence may go some way to demonstrating the factum but it will still be necessary to show the animus.

As was provided in the case of Ramsay v Liverpool Royal Infirmary where the court declared that, the deceased had not acquired domicile even after living in Liverpool for thirty-six years.

Also the same was stated in several other cases such as Winans v AG and Jopp v Wood where parties in both cases had stayed in their places for a long time but failed to acquire domicile.

An intention to reside (animus) to continue living there permanently or for an unlimited period of time, to decide if a person has the intention to take a place as his/her domicile, the conduct of the person and the surrounding circumstances are taken into consideration.

The intention of the person must not be subject to any conditions such as an intention to reside for a definite period, for example, six months, and then leave or an intention to reside in a territory until a definite purpose is achieved, for example, to leave when a particular project is completed such as termination of his/her employment.

Such conditional animus is not sufficient to establish domicile as it was provided in the case of Cramer v Cramer, where a woman with a French domicile of origin went to England intending to remain there and marry an Englishman who at that time was married.

Her intention to remain was conditional on both herself and her proposed husband obtaining divorces and on their relationship continuing but since such did not happen she failed to acquire domicile.

These factors have to operate together in order to establish domicile, as such was stated in the case of Winans v AG, where it was provided that though the deceased had stayed in Britain all his life the court had established that he had not acquired a domicile of Britain since it was proved that he lacked intention due to his hatred of Britain and after examination in detail of his life.

Also in the case of Jopp v Wood, where it was held that the deceased had not acquired a domicile in India even after living there for twenty-five years since he had the intention of one day returning to his land of birth. Hence the duration of the residence will not be an essential factor in establishing a domicile but rather should be supported by the intention of the propositus.

Hence in most cases, the emphasis is on the animus rather than the duration of residence.

Thus even a short period can be sufficient if there exists an intention to reside.

The fact that a brief residence may be sufficient to establish a new domicile is important if the domicile has to be established shortly after an individual has arrived in a new country in which he intends to live permanently.

For example, in the case of White v Tennant, where a family was moving home. The man abandoned his home in State A and moved about half a mile to his new home in State B.

Having put their belongings in the new house, the family returned to their old State as the new house was not ready to inhabit. When the man died during the night the court decided that he died domiciled in State B and not in State A since residence and intention were proven unequivocally.

Hence an individual’s presence in the state and intention to make a home suffices to establish a domicile even if no particular locality is chosen by him/her for home, it may be a rented house or a hotel all will be sufficient to establish domicile.

It is necessary to produce unequivocal evidence of both the facts of residence and the intention to permanently reside.

This is another form or type of domicile, under this domicile, a person’s domicile will depend on a person on whom he depends, this domicile conferred a domicile to the legal dependant

This is usually done by the operation of law. It covers those people who are incapable of forming a requisite intention to acquire a domicile of choices like young children and mental incapacity.

Before the Domicile and Matrimonial Proceedings Act 1973 in England married women also formed a part of a dependant person, the domicile married woman was dependent on the domicile of his husband but after the said Act come into force a marriage woman’s domicile was not dependent on her husband, section one of the said Act provides that;

the domicile of a married woman as at any time after the coming into force of this section [1 January 1974] shall, instead of being the same as her husband’s by virtue only of marriage, be ascertained by reference to the same factors as in the case of any other individual capable of having an independent domicile.

For young children, it’s generally established that a person acquires a domicile of origin at birth based on parentage and this domicile is never lost completely as already discussed, as a domicile of a child depends on his parent it can be termed that his domicile is dependency one, and as already indicated from the case of Udny v Udny the domicile of a legitimate child depends on his father while of the illegitimate child is based on the mother.

In his book Conflict of laws, John O`Brien summarizes particular cases concerning children and the domicile of dependency.

He said that; After the mother of an illegitimate child has died, or both parents have, in the case of a legitimate child, the child will continue with the domicile of dependence until he is capable of acquiring an independent domicile.

A child is capable of acquiring an independent domicile when reaching the age of 16 or if he marries under that age.

In cases of a legitimate child whose parents are living apart and where the child has a home with the mother, then the child will acquire the domicile of the mother and, in such a circumstance, if he lives with the father he will acquire the domicile of the father

In situations where the father dies, the domicile of the child will normally follow that of the mother, save in those situations where the mother leaves the child with a relative when moving to a new country.

In the case of an adopted child, such a child will be treated as if he were the natural child of his adopted parents. Thus, from the date of adoption, if not earlier, he will have the domicile of his parents.

Mentally incapable persons, general a mental incapability person cannot acquire a domicile of choice and as a general, the rule retains the domicile which he has when he became mentally incapable.

Since such a person cannot exercise any will he or she either acquires or lose domicile and nor can the domicile be changed by a person taking charge of or caring for a mentally disordered person.

For instance, D who is domiciled in India becomes insane and is sent to England, he retains his India domicile so long as he remains insane.

Also in the case of Crumpton`s Judicial Factor v Finch Noyes, D was born with the domicile of origin of Barbados, his father died later on, and shortly after his mother resumed her domicile of origin and take D with her, D continue o reside in Scotland till he became insane and was placed in Scotland institution, he died later on without recovering his sanity, D was regarded as a person domiciled in Scotland.

From the above discussion, we may draw that factors that are taken into account in establishing a domicile of dependency are the domicile of a person on whom the dependent person depends.

As a general rule to constitute domiciles residence of any person or propositus must be voluntary a matter of free choice and not of constraints but there are some exceptions where some situations where it’s not voluntarily, such a situation may apply to various classes of people as follows;

Imprisonment in a foreign country raises doubt if such a prisoner freely accepts to reside in a place where he might be transported or exiled, it brings doubt as to whether he can retain the domicile that he possessed before his confinement

These are people who settle in a foreign country for the sake of their health and not merely for the purpose of convalescence.

Such a person must have an alternative either to stay or to go. Unfortunately, such a choice is already made due to the concern for his health no matter what he would definitely decide to go to such a country so as to be cured whether he likes it or not.

Freedom of choice is also affected when a man finds it desirable to flee the country to avoid his creditors.

Fugitive from justice; It’s also an example of involuntary residence in a new country.

If a man leaves his domicile of origin so as to escape the consequences of a crime, the natural inference is that he has left forever hence it favors the acquisition of a fresh domicile in the country of refuge.

For example, in the case, Moynihan v. Moynihan whereby a propositus, who had left the UK to avoid arrest on serious fraud charges had at his death acquired a domicile of choice in The Philippines.

People who moved/ran away from their domicile of origin due to various reasons such as political problems tend to acquire new domiciles which mostly the new intended/counted to but due to such problems, they are left with no alternative.

For example refugees from Rwanda who were hosted by Tanzania haven referred to as the new domicile most of them find themselves forced to stay here.

As pointed out above connecting factors include domicile, nationality, and residence. Here I will explore the connection and relationship that exists between domiciles and the other two connecting factors, which are nationality and residence.

Since domicile means a permanent home of a person, it follows that one cannot be said to have a permanent home without an actual or physical presence in the place in question. And for the purpose of the law, residence means physical presence in a particular country.

Cooton LJ in Re Marret observed that; The law as I understand it is this, that the domicile of origin clings to a man unless he has acquired a domicile of choice by residence in another place with an intention of making it his permanent place of residence.

One cannot be said to be domiciled in a particular country without establishing whether he is a resident of that given country.

A long residence is a fact that may raise the inference that a person intends to reside in a given country and hence constitute a domicile.

On top of that both domicile and residence are connecting factors used to determine the personal law in private international law; it is mostly applied by countries following the civil legal system.

Also in case of abandonment of domicile, the same element has to be proved, which is the physical removal from a country with the intention not to return to. That is a coincidence of non-residence and intention not to reside.

In the case of Bell v Kennedy, the court was of the view that, for a person to acquire a domicile of choice it is necessary to produce unequivocal evidence of both fact of residence and an intention to permanently reside. Therefore there is a clear connection between domicile and residence as a connecting factor as indicated above.

Nationality and domicile are both connecting factors; this is because the latter indicates a connection with a state while the former indicates a connection with the law.

The relation available is that both nationality and domicile have been advocated by writers to be methods to determine the personal law, that is to say, nationality can be used as an alternative to domicile when it comes to determining the person in case of conflict of law.

It was firstly introduced in France in 1803 as a consequence of the code Napoleon. Now it is adopted in most continental European countries, South American states and Japan uses nationality to determine personal law instead of domicile.

The discussion has scrutinized and explored the concept of domicile as a connecting factor.

Furthermore, it has explained the factor that is taken into consideration by the court to determine the domicile of a person so as to be able to pinpoint the legal system to which a person is connected.

No one can live without a domicile and normally no one can have more than one that is a unique feature that makes the court prefer domicile over nationality and residence.

Read also: What is classification in Private International Law?

CASES

Bell v Kennedy1868 LR 1 Sc & Div 307;6 Macq 69

Cramer v Cramer1987] 1 FLR 116

Crumpton`s Judicial Factor v Finch Noyes 1918 S.C. 378

Hepburn V Skirving 1861 9 W.R. 764

Jopp v Wood(1865) 4 De GJ & Sm 616

Lawrence v Lawrence1985

Mark v Mark [2005] UKHL 42

Moynihan v. Moynihan [1997] 1 FLR 59

Ramsay v Liverpool Royal Infirmary[1930] AC 588

Re Martin [1900]

Re Marrett (1887) 36 Ch D 400, CA.

Udny v. Udny (1869) 1 LR Sc. & Div. 441 HL

Whicker v Hume (1858) 7 HL Cas 124

White v Tennant(1888) 31 W Va 790.

Winans v Attorney General[1904] AC 287

BOOKS

Collie, J. Conflict of Laws 3rd ed, Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, (2004).

Collins, L, Ed. Dicey, Morris and Collins, The Conflict of Laws Vol 1, 14thed, London; Sweet

&Maxwell. (2006).

David, MacClean and another, Morris, the conflict of laws 6th ed, London; sweet &

Maxwell. (2005)

North, P &J. Fawcett, Eds. Cheshire and North`s Private International 13th ed; New Delhi;

Oxford University Press. (2006).

O`Brien, J. Conflict of Laws 2nd ed. London; Cavendish Publishing Limited, (1999)